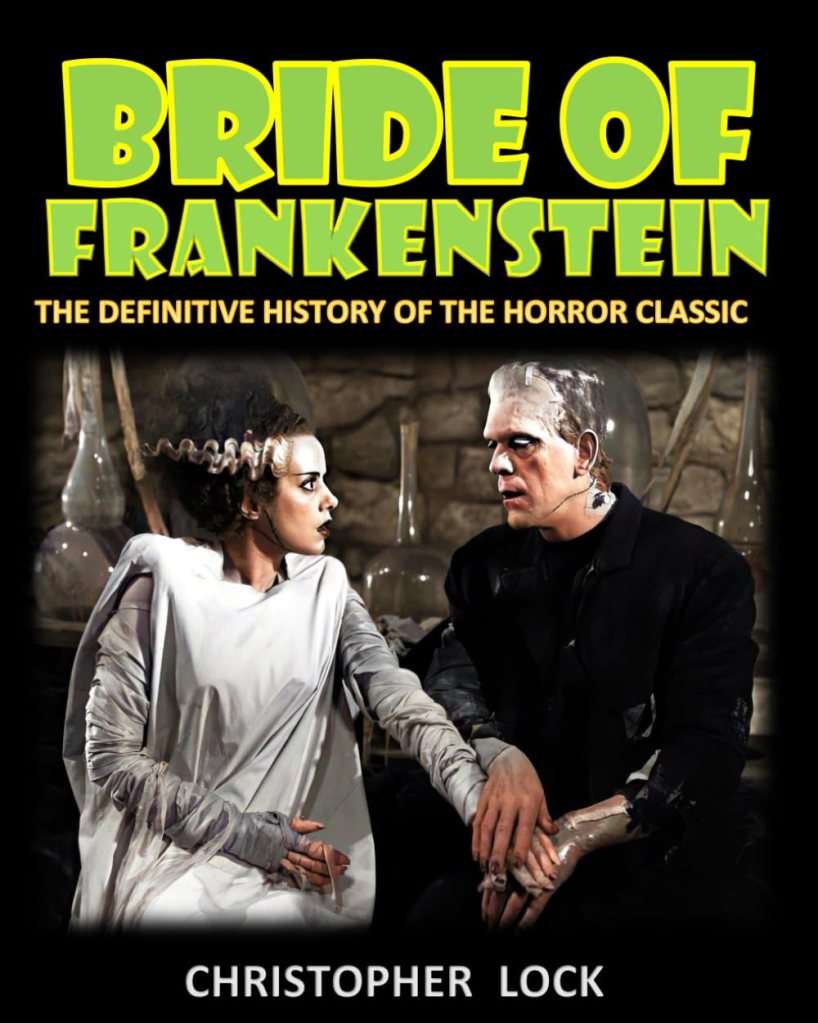

Bride of Frankenstein: The Definitive History of the Horror Classic

Published by CenterLine Publishing & Consulting LLC, 2024. 422 pages

By Christopher Lock

For a film that is making its 90th Anniversary this year, there is a lot that has been written about Bride of Frankenstein (1935) over those nine decades. In fact, I have a couple of books solely dedicated to this title, not to mention more than a few that cover the Universal classic horror titles of the ’30s in general. Of course, when you see one with the subtitle “The Definitive History of the Horror Classic” it does grab one’s attention.

Who am I kidding? It’s a book on one of the most famous horror films ever made. Of course I’m going to add it to my library! So, the real question is . . . is it the “definitive history”? And is it worth adding to your own library?

The author has a lot of information in here, not just on Bride, but the original film as well, and even including some info on Mary Shelley and her original novel. There could be an argument on why it covers that stuff when the book is about Bride, but I do agree that you need to cover those first before you get to the famous sequel. Though I did find it a little strange that while going over the beginning, when the original Frankenstein was in the early stages, the author mentions the early scripts by Balderston and Webling, but nothing is mentioned about Robert Florey, who was the one that brought the original idea to Universal, with the intent of directing it. A minor quibble.

And I think a minor quibble here or there is the only negative thing I can say about this book. Sure, there are bits of information relayed twice in the book, in different chapters, or even on the following page. Same with some biographical information, some is repeated. Or that the author uses almost 70 pages to go through the entire film with a play-by-play of what is happening. If we’ve bought the book, most likely we’ve seen the movie. And an index would have really been nice.

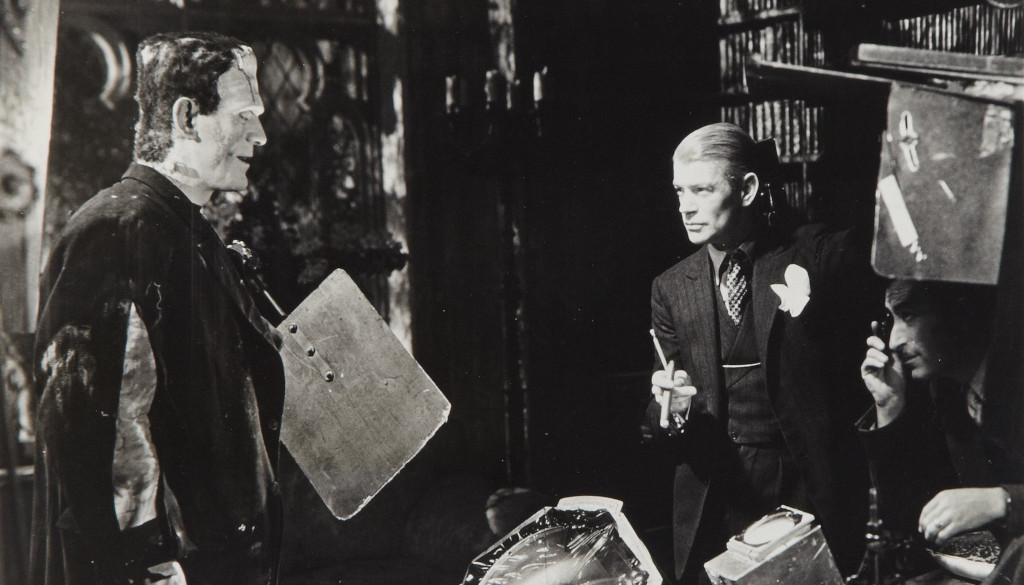

But beyond that, Lock really spends a lot of time with the production of the film, and going through what was involved, and who was involved in it. He spends time giving some background on lesser-known talent that worked on the film, such as the editor, the ones building the miniature sets, and to the cinematographer John J. Mescall, which he gives a lot of credit in how things were shot. Everyone knows about the genius of makeup man Jack Pierce, which he does cover as well, but it was nice to see others getting some spotlight as well. As all movie fans know, it takes quite a few to create a film to begin with, so when it is as magical as Bride, there’s a lot of credit to go around, and Lock does that, which is very much appreciated.

There are also those things that some might consider so obvious to some, but to others it may have gone unnoticed. Lock gives a great comparison between the opening shot with Mary, Percy, and Bryon, all sitting on the couch after Mary pricks herself with her sewing needle, and with the same shot with the characters of Henry, Pretorius, and the bride are positioned at the end. Can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen the film but never noticed that. You can always learn something new.

Lock also does an excellent job when discussing certain scenes or even subjects that historians love to talk about and debate the “real meaning” behind it, especially when it comes to James Whale. Lock will give the different sides or say one of the common takes on a scene but then states “or at least that’s what some film historians have claimed.” He’s not calling bullshit on either side but just saying that it really is a matter of opinion. In fact, there is a great paragraph near the end of the book where Lock sums up all the thoughts and hidden meanings and messages that may or may not be in the film, and I think he nails it perfectly.

“But as with any philosopher or interpretive party, one can analyze every word and frame of Bride of Frankenstein until they’re blue in the face. Double meanings, suggestions, and insinuations can be twisted and construed to represent anyone’s point of view. Most certainly, Whale liked nothing better than to take creative risks, push the edge of Hollywood censorship, and shock the audience. But exactly how far he went to achieve that in Bride, and how deeply he implanted religious and gay themes may never fully be understood. The only true way to determine Whale’s intent is to ask him. As that is not possible, we can only go by what those closest to him revealed.”

Priced at $25 and over 400 pages, I would recommend this book to any fan of the Universal classics, or horror films in general. While the debate on whether Bride is better than the original Frankenstein will go on forever, there is always more to learn about both. And this volume will help you do that.